Botanologías (2022)

Es.

“Botanologías” viene de una antiguo nombre dotado al estudio de las plantas y sus utilizaciones medicinales y mágicas en la tradición europea antes de la estandarización botánica como parte de la empresa ilustrada. La botanología recoge las relaciones simbólicas, culturales, materiales y sobrenaturales de los cuerpos vegetales entendidos no como taxones a ser categorizados a través de la descripción visual sino como entidades activas en los cuerpos y tejidos sociales humanos. Esta serie explora lo vegetal desde este enfoque enterrado por una visión desencantada y “apolítica” de los cuerpos botánicos. Desde esta perspectiva, se reinterpretan mitologías de base para la tradición occidental para dotar una ficción paralela donde lo vegetal devele puntos de fuga narrativos aliándose a otras subjetividades humanas igualmente desterradas en el proceso de modernización.

En.

"Botanologies" derives from an ancient name given to the study of plants and their medicinal and magical uses in the European tradition before botany was standardized as part of the Enlightenment project. Botany, in this sense, gathers the symbolic, cultural, material, and supernatural relationships of plant bodies—understood not as taxa to be categorized through visual description, but as active entities within human bodies and social fabrics. This series explores the vegetal from this buried perspective, one overshadowed by a disenchanted and "apolitical" view of botanical bodies. From this standpoint, foundational mythologies of the Western tradition are reinterpreted to create a parallel fiction in which plants reveal narrative lines of flight, allying themselves with other human subjectivities likewise displaced in the process of modernization.

Las Dos Muertes de Jacinto (2022)

Estudios queer – Botánica – Mitología – LGTBIQ+ - Ficción

La historia de San Sebastián es la de un soldado romano condenado a muerte por la confesión de su fe cristiana. Su ejecución se da siendo atado a un árbol y muerto por flechas. Posteriormente, el soldado romano fue canonizado y durante los siglos XVIII y XIX, en Europa, su imagen se volvió un icono de la sensualidad masculina y símbolo de un secreto inconfesable. Paralelamente, el mito de Jacinto y Apolo cuenta un amor helénico imposible que se encuentra con la muerte súbitamente. Separados, Apolo dota a Jacinto de la eternidad en la tierra a través una flor como conmemoración. Ambas historias crean alianzas narrativas entre el deseo homosexual y las figuras vegetales. Los vínculos subterráneos entre las plantas (especialmente las delicadas pero sexuales flores o los vigorosos troncos) y la identidad queer aparecen sutilmente para levantar preguntas sobre estos los lazos ocultos a la vista y su exhuberancia y diversidad. El video en doble canal contrapone las figuras históricas (modelo 3D de una escultura de madera policromada alemana de principios del siglo XV de San Sebastián martirizado) con los cuerpos vegetales (modelo 3D de una flor de jacinto). El video avanza mientras ambos cuerpos se desarman y nos permiten transitar lo que hay debajo de la “corteza” de sus formas. Lo vegetal y lo disidente se entretejen bañados por una luz rosácea. La figura trágica del amante homosexual encuentra en lo vegetal un modelo de existencia que ha sido un compañero agridulce en la historia de lo queer en la tradición visual occidental.

En.

The Two Deaths of Hyacinth.

Saint Sebastian was a Roman soldier sentenced to death for the confession of his Christian faith. He was tied to a tree and killed by arrows by order of the emperor Diocletian. Later, he was canonized and during the 18th and 19th centuries in Europe his image became an icon of male sensuality and one of an unspeakable secret. At the same time, the myth of Hyacinthus and Apollo narrates an impossible Hellenic love that suddenly meets death. Separated, Apollo endows Hyacinth with eternity on earth with a flower as a commemoration. Both stories create narrative alliances between homosexual desire and plant figures. The underground links between plants (especially the delicate but sexual flowers and vigorous trunks rising) and queer identity subtly appear to raise questions about ties hidden in plain sight, exuberance, and existences that survive if they escape the watchful eye of the hegemonic gaze. The dual channel video contrasts historical figures (3d model of a German polychrome wooden sculpture from the early 15th century) with plant bodies (3d model of a blooming hyacinth). The video progresses as both bodies disarm and allow us to walk through what is under the "crust" of their forms. The plant and the dissident intertwine bathed in a pinkish light. The tragic figure of the homosexual lover finds in the vegetal a model of existence that has been an unrecognized companion in the history of queerness in the Western visual tradition.

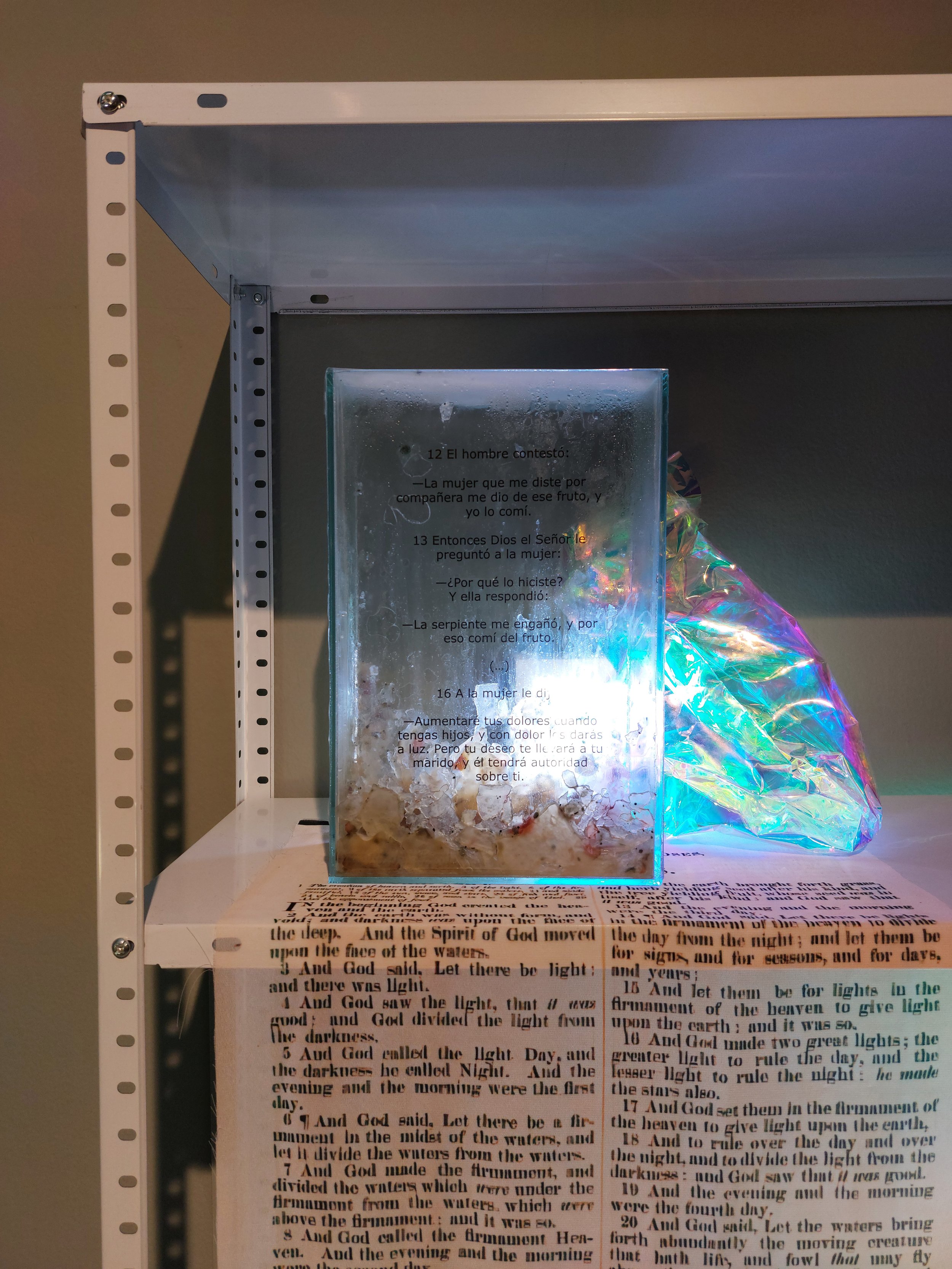

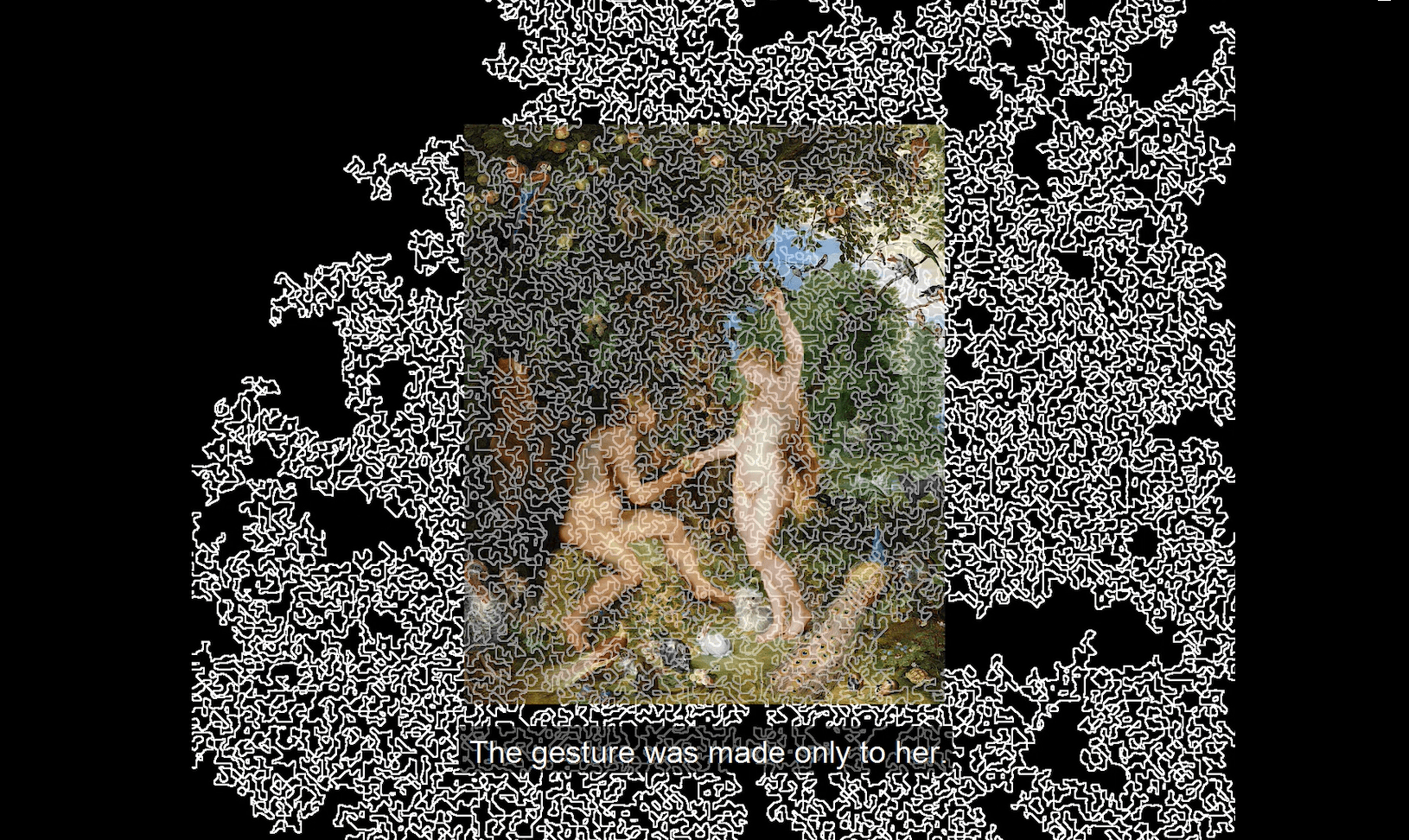

Havva Botrus (2022)

Micología – Mitología – Estudios de Género – Historia del Arte

Eva (Havva) fue creada a partir de la costilla del primer ser humano creado por Dios en la tradición religiosa abrahámica. En la biblia, Eva es seducida por la serpiente del árbol de la sabiduría y prueba el fruto prohibido del conocimiento: una manzana. Instantáneamente, Adán y ella son expulsados del paraíso para vivir vidas mortales en condiciones de entropía e incertidumbre. Este relato ha formado profundamente la visión misógina occidental culpando a la mujer de las desgracias de una vida biológica y terrenal. Sin embargo, ¿Qué sucede si en realidad la figura de Eva nos liberaba de un plan divino de excesos y fantasía? El hongo Botrytis Cinerea es muy común en frutas, entre ellas la manzana (en realidad, en algunas representaciones medievales, el fruto prohibido no es una manzana, sino un hongo). Este hongo anula las defensas del fruto y se alimenta de sus células muertas. El hongo en la manzana del conocimiento aparece como el verdadero desencanto del mundo. En el video una escultura de piedra (La Tentation d'Ève - Gislebertus) empotrada en la catedral de Saint-Lazare d'Autun en Francia (aprox. 1130) gira sobre sí misma abriendo capítulos discursivos: Eva como madre, como esposa y finalmente, como micelio. Igualmente, tres pinturas alrededor del mito de Eva se despliegan (una ilustración medieval de Eva y la serpiente de 1350, un óleo de 1520 de Lucas Cranach el Joven y un óleo de Brueghel y Rubens de 1615). Los recursos históricos ayudan a desplegar la narrativa crítica alrededor del mito de Eva y como puede ser convertido, revalorando la podredumbre del paraíso, en una historia de consciencia terrenal. En el Edén nada moría, ningún animal ni planta depredaba a otro; se trata de una maqueta de fantasía divina con la condición de nunca reconocer su falsedad. Eva abre los ojos y ve un mundo fungal, aquel que habitamos. Si el paraíso prohibía el conocimiento y la autoconciencia, Eva fue el primer ser humano en ver al Edén como una ideología hueca; una maqueta de Dios para Adán donde ella fue lo último en ser creado. Eva es la madre del pensamiento crítico en un mundo fungal.

En.

Havva Botrus.

Eve (Havva) was created from the rib of the first human being conceived by God in the Abrahamic religious tradition. In the bible, Eve is seduced by the serpent of the tree of wisdom and tastes the forbidden fruit of knowledge: an apple. Instantly, she and Adam are expelled from paradise to live mortal lives in conditions of entropy and uncertainty. This account has deeply shaped the western misogynist view by blaming the woman for every misfortune of a biological and earthly life. However, what happens if in reality the figure of Eve frees us from a divine plan of excess and fantasy? The Botrytis Cinerea fungus is very common on fruits. This fungus nullifies the defenses of the fruit and feeds on its dead cells. The fungus in the apple of knowledge appears as the true disenchantment of the world. In the video, a stone sculpture (La Tentation d'Ève - Gislebertus) embedded in the Saint-Lazare d'Autun cathedral in France (approx. 1130) spins around itself, opening discursive chapters: Eve as mother, as wife and finally as mycelium. Similarly, three paintings around the myth of Eve are displayed (a medieval illustration of Eve and the serpent from 1350, an oil painting from 1520 by Lucas Cranach, and an oil painting by Brueghel and Rubens from 1615). Historical resources help to unfold the critical narrative around the myth of Eve and how it can be turned, under critical analysis, into a story of earthly consciousness. In Eden nothing died, no animal or plant preyed on another, a model of divine fantasy with the condition of never recognizing its falsehood. Eve opens her eyes and sees a fungal world, the one we inhabit. If paradise forbade knowledge and self-awareness, Eve was the first human being to see Eden as a hollow ideology, a model of God for only Adam where she was the last being to be created. Eve is the mother of critical thinking in a fungal world.